How did mechanical-watch king Rolex deal with the arrival of quartz in the 1970s? What follows is an excerpt from the book “Electrifying the Wristwatch,” by WatchTime contributor Lucien Trueb. The book, illustrated with photos of pieces from replica watches uk collectors Günther Ramm and Peter Wenzig, tells how quartz-watch technology evolved.

André Heiniger, second Rolex president and successor of the founder Hans Wilsdorf, was a true visionary. His opinion was that the originally very costly quartz watch would soon be totally banal. This already had happened with transistor radios, TV sets, and pocket calculators.

Top-quality mechanical movements would always remain expensive and exclusive due to the large amount of highly qualified labor that is required for manufacturing the parts and assembling them. The inescapable fact that a mechanical device can only tell time approximately could be easily hidden by writing “Superlative Chronometer, Officially Certified” (i.e., the COSC certificate) on the dial. This means a daily rate of plus-six/minus-four seconds per day. In due time, every watch brand in the “upscale” sector copied Heiniger’s concept. Wealthy people don’t need an instrument that tells time: they want a beautiful and exclusive object on their wrist.

“Electrifying the Wristwatch,” a large, amply illustrated and encyclopedic book by Lucien Trueb, gives quartz watch history some much deserved attention.

Analog Quartz Calibers

Rolex totally ignored microelectronics until the early 1970s; as a shareholder of CEH [Centre Électronique Horloger] it obtained 320 Beta 21 calibers out of the 6,000 that were actually produced. Furthermore, Rolex bought 650 pieces of the Beta 22 version produced by Omega; they are known as the Rolex Caliber 5100. In addition, Rolex Bienne was part of the consortium that financed the Neosonic-AFIF adventure with the known, sad end. Rolex Geneva was not involved.

After this easy beginning, it was quite clear to Heiniger that Rolex had to be independent in the realm of microelectronics too. In 1971 he hired René Le Coultre (b. 1918) who was then technical director of the Fédération Horlogère (FH). Le Coultre headed the technical department with a staff of 49, including 10 engineers. His first activity was to set up a top modern electronics lab with 13 people. He was then in a position to design quartz equivalents of Rolex’s mechanical calibers. This was not too difficult: at that time, Rolex only produced a ladies’ watch movement with two hands, a version with three hands, and a men’s luxury replica watches caliber with sweep seconds hand and date or day/date.

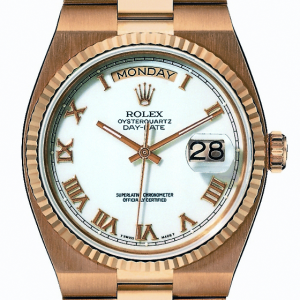

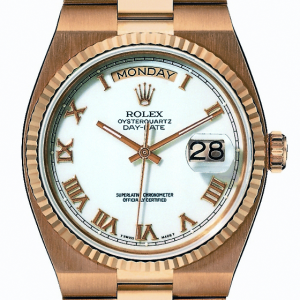

The chronometer-rated Caliber 5055, which had a day and date

The quartz equivalent of the men’s watch caliber came in two versions. The functions of Caliber 5035 (29.75 mm by 6.35 mm) were hours, minutes, sweep seconds hand, and date. Caliber 5055 (29.75 mm by 7.11 mm) featured the day/date function, which explains the difference in height. The quartz resonator’s frequency was adjusted with a trimmer capacitor covering a range of plus or minus two to three seconds per day. The rate was less than one minute a year, i.e., 0.17 second per day. The Rolex quartz calibers were launched in 1977; product life was an amazing 26 years. Both calibers featured a tuning-fork-type, mechanically cut 32-kHz quartz resonator made by NDK in Japan. It was replaced at the earliest possible date by the photolithographic type supplied at first directly by Statek in Orange (California) and, later on, by Micro Crystal in Grenchen. ETA had signed a licensing agreement with Statek; delivery from Grenchen started in 1978, Rolex was one of the earliest customers.

The CMOS integrated circuit Rolex needed was supplied by Ébauches Électroniques Marin, while the anchor-type motor was purchased from FAR (Fabriques d’Assortiments Réunies). Silver oxide batteries were available from the Swiss Renata company as well as from American and German suppliers. Total production of the Caliber 5035/5055 is exactly known: 105,097 – not terribly much considering that the product life was 26 years! Each and every one of them was certified by COSC as an electronic chronometer. Those movements were decorated with Geneva stripes exactly like a mechanical Rolex movement; they featured 11 jewels. In the mid-1980s, the Rolex quartz movements were thoroughly redesigned and modernized. The result of this work was Caliber 5235 (with date) and 5255 (with day/date). Caliber 5235, with a diameter of 28.10 mm and a height of 5.40 mm, was equipped with a Faselec chip that included digital frequency tuning, a Lavet stepping motor from ETA and an 11.6-mm three-volt lithium battery. The same applied for the day/date Caliber 5255 (29.90 mm by 5.80 mm). These were among the best conventional quartz calibers that were ever designed – unfortunately, they never saw mass production.

Instead, the famous Oysterquartz watch models were equipped with the quartz Caliber 5035 and 5055. They sold very well: they were less costly and at least 10 times more accurate than the mechanical Oyster. However, the cases were somewhat different: Heiniger would not tolerate that a quartz cheap replica watches looked similar to a classic mechanical Rolex. The production was only about 4,000 pieces a year – not much marketing effort was made to promote the Oysterquartz – aside from a very original ad showing both Everest climbers Edmund Hillary and Reinhold Messner. Hillary had worn a mechanical Rolex on his ascent; Messner an Oysterquartz. The text just said: “In 1953 they needed Rolex watches and oxygen to climb Everest. In 1978 they did it without the oxygen.” The retailers were not at all motivated to sell the Oysterquartz, as the cost was significantly less than the mechanical Oyster and therefore meant less profit. There are tales about potential customers who literally had to beg for an Oysterquartz.

Rolex made just 4,000 Oysterquartz watches per year.

The Rolex quartz caliber for ladies’ watches (Caliber 6035) with sweep seconds hand and date disk had the exact same dimensions as the Ladies’ Datejust (19.79 mm by 5.00 mm). The frequency of the 32 kHz Micro Crystal tuning fork quartz resonator was fine-tuned with a trimmer. The CMOS circuit was purchased from Faselec, the Lavet motor from Seiko. The energy source was a 7.90-mm silver oxide battery. Thirty prototypes of Caliber 6035 were built but there was no mass production. However, Cellini quartz models were equipped with Caliber 6620 (no seconds hand): this caliber was directly derived from Caliber 6035. In July 1983, 20 prototypes of Caliber 6620 were available for tests that took a long time; serial production started as late as 1987. The diameter was 8¾ lignes (19.80 mm); the height 2.5 mm. The parts were standard Rolex replica uk issue, as mentioned above. In 1990, production of Caliber 6621 started; this time the trimmer was replaced by an inhibition circuit. Production of this caliber continues to this day; total production so far is well over 100,000 pieces.

Rolex developed several technically advanced quartz movements that never got beyond the prototype stage. The most interesting of them certainly was a thermo-compensated quartz caliber that was developed in 1985. Design studies were made with extremely stable high frequency (1.2 MHz and 2.4 MHz) quartz resonators with the ZT cut. The CEH produced those resonators and delivered 1,000 pieces in 1984. In 1986, Rolex built 50 prototypes but there was no production, even though the yearly rate was just a few seconds. Another very ingenious quartz caliber with a perpetual calendar had the same fate. It was set in a particularly easy way; it also featured a 2.4 MHz quartz resonator with ZT cut as well as a standard 32 kHz resonator. As the ZT quartz and its divider circuit needed a lot of power, it was only switched on every 10 minutes for 10 seconds in order to set the 32 kHz frequency. An extraordinary rate and a battery life of 10 years were achieved with a three-volt lithium battery that measured 22.0 mm by 2.5 mm. The 30-mm caliber featured three motors for the seconds, the minutes and hour, and the day/date function, respectively. This design was patented; the patent became public domain in 2011. A test series of 400 pieces was assembled, but there was no production; none of those prototypes ever left the Rolex premises.

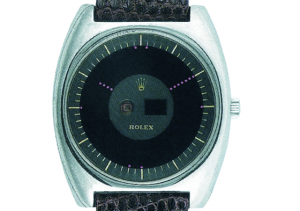

The Pseudo-Analog Caliber FAN

In the mid-1970s, Heiniger let it be known that Rolex was interested in new and original quartz watch designs. His technical director René Le Coultre immediately recalled the CEH design of caliber Delta, a pseudo-analog, solid state movement with light emitting diodes and a solar cell power supply, for which no watch brand so far had shown any interest. This was the starting point of the FAN project (FAN = Forme Analogique). The Rolex electronic team was enthusiastic, even though chances were small that such a watch would ever be produced in series. Working for Rolex presupposes strong nerves and the will to produce “l’Art pour l’art.” Engineers who want to see their designs cut into metal immediately should not work for Rolex.

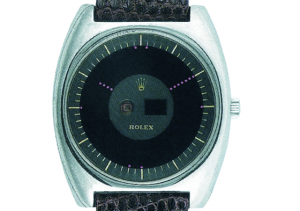

A Rolex FAN model with pseudo-analog display

In 1975, Le Coultre “borrowed” Raymond Vuilleumier from the CEH in order to find vendors in the United States who might become suppliers of parts for the FAN caliber. Vuilleumier had worked for six years with General Electric and had built up a comprehensive network of microelectronic firms all over the U.S. Furthermore, Vuilleumier had been in charge of the Delta caliber project. Le Coultre also decided to take along his electronics specialist Edmond Zaugg, who also was an enthusiastic radio amateur. The trio traveled to the United States three times between 1975 and 1976. They were received everywhere with utmost courtesy: the name Rolex opened any door. The subcontracts for FAN could be placed with the best qualified firms. Thus, the FAN-dial module was supplied by Hewlett Packard in Palo Alto, and the multiple-layer connection module for the light emitting diodes was designed by Ceramic Systems in Sorrento Valley near San Diego. The CEH was responsible for the integrated circuit; Rolex would provide system integration and assembly.

The CEH Delta concept thus evolved into the cheap Rolex replica FAN Caliber 7035; the dimensions were 30.0 mm by 8.00 mm with a pseudo-analog LED display. The hours were displayed with four light emitting diodes in a row, the minutes with seven such diodes, the seconds with a set of 60 diodes along the edge of the dial: they were lit one after the other within a minute in the clockwise direction. Thus, a radial matrix of 60 by seven LED was needed. As a help to the user, a pusher was provided that lit two diodes at 12 o’clock and one diode at 3, 6, and 9 o’clock. The date indication, consisting of the conventional seven-bar LED matrix, was arranged in the center of the dial. In order to energize it for two seconds, a key had to be pushed twice; a third pulse switched on the number of the month. A photodiode next to the date display controlled the intensity of the LED in function of the surrounding light level. There was no need for solar cells, as the continuous operation of this movement was unthinkable: a key to switch on the display Pulsar-like was indispensable. Rolex built just five prototypes with the components that were supplied by the CEH and the American companies mentioned above; they worked in August 1978. Developing the FAN had cost a cool million Swiss francs, but Rolex was not much poorer for that. When Heiniger decided that such a watch did not correspond to the Rolex product philosophy, the FAN project was cancelled and the development costs were written off. Publications on this subject were not authorized.